Stories are everywhere. From our childhood, stories have played a major part in our understanding of the world and humans. We made up stories and imagined that when god cries, it rains; we imagined the TV people are actually inside the box. Stories are a great tool to build our imagination but is that enough?

In today’s world, every human-depended organizations uses stories to get their subject closer to people. Advertisements, TikToks, Stand-Up comedies, every thing needs a story to reach people. By inching towards humanism, passion, emotions and connections we lost rationalism. That is exactly why people should tread carefully on social media.

Read More: Top 25 Movies Based On Books

Why Should One Be Beware Of The Storification?

Literary Theorist Peter Brooks notes that there is a growing trend in American culture called “storification.” In his book, ‘Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative’, he argues that we are relying too much on stories, since the turn of millennium. The reliability is to understand the world around us easily. This has resulted in a “narrative takeover of reality” that affects nearly every form of communication. It affects the way doctors interact with patients, how financial reports are written, and the branding that corporations use to present themselves to consumers.

While these communications are getting affected, other modes of expression, interpretation, and comprehension, such as analysis and argument, have fallen by the wayside. The public fails to understand that many of these stories are constructed through deliberate choices and omissions, and this negligence is dangerous. Enron, for instance, duped people because it was “built uniquely on stories—fictions, in fact … that generated stories of impending great wealth,” Brooks writes. People are falling for tales the perpetrators spun. Since we are too much integrated into the storification mechanism, the close reading and skepticism have left our mind systems.

Why Critical Analysis Is Even More Needed In The Age Of Internet?

The ability to read critically and recognize the way a narrative is constructed is even more important now in the age of internet. A more attentive and analytical reading is essential to grasp the internet. If amid social upheaval we use stories to make sense of our world, then on the internet we use stories to make sense of ourselves.

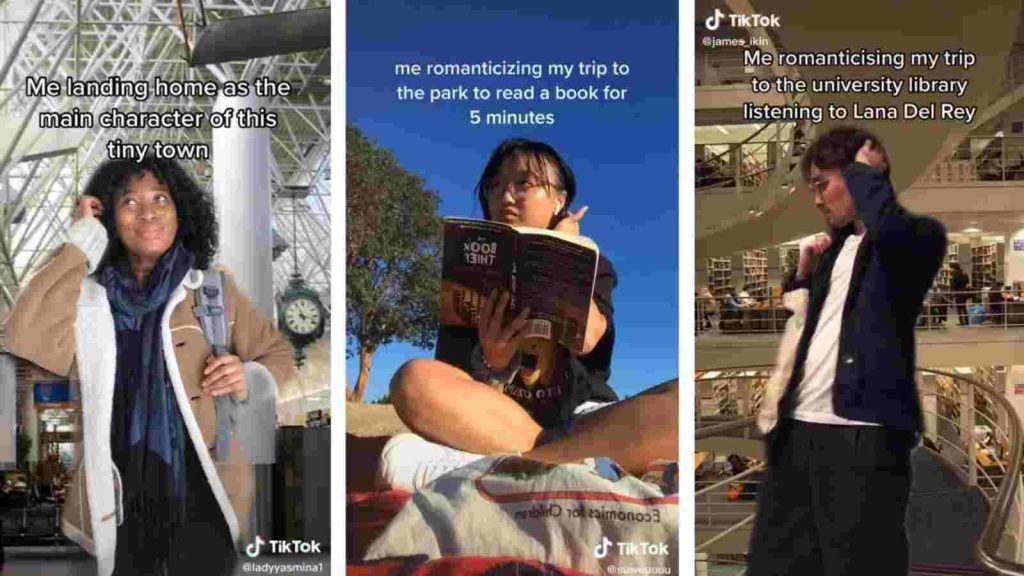

Bo Burnham, in an interview for his 2018 movie, ‘Eighth Grade’, said that when it comes to the internet, talking heads focus too much on social trends and political threats rather than on the “subtler,” less perceptible changes it’s causing within individuals. “There’s something interior, something that’s actually changing our own view of ourselves,” he said. “We really do spend so much time building narrative for ourselves, and I sense with people that there was a real pressure to view one’s life as something like a movie.”

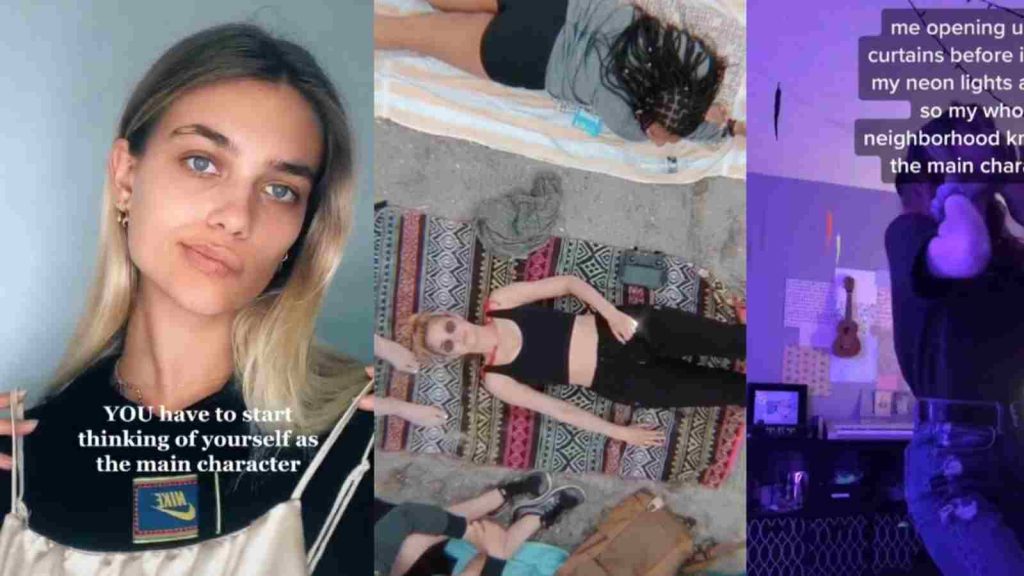

Just look at TikTok, where storytelling has become a lingua franca. In videos on the app, users encourage one another to “do it for the plot” or to claim their “main-character energy”—and, crucially, to film the results. One TikTok tutorial shows users how to edit a video to “make your life seem like a movie.” In another video, a forlorn teen stares into the camera above the text, “i know i’m a side character, i have no purpose except to sit and wait for my next scene.” Here, and in most other corners of the internet, narrative taxonomy prevails. We’re telling ourselves stories in order to live, yes, but we’re also turning ourselves into stories in order to live.

On Instagram, “Stories” allow users to broadcast moments and experiences to their followers, and it’s tempting, one Mashable article argued, to rewatch your own—to view your life in the third person, packaged and refracted through a camera lens. “What do we want more,” Burnham asks in his 2016 special, Make Happy, “than to lie in our bed at the end of the day and just watch our life as a satisfied audience member?”

Are We Telling Stories Because It’s A Social Act?

Social media hinges on storytelling because telling stories is, in Brooks’s words, “a social act.” This isn’t inherently bad, but it’s vital to be aware of artifice and the spin we put on our lives in public. As narrators of our own lives, Brooks writes, “we must recognize the inadequacy of our narratives to solve our own and [others’] problems.” Pulling from Freudian psychoanalysis, Brooks concludes that telling stories should be a tool we use to understand ourselves better rather than a goal in and of itself.

Today, stories have become ubiquitous, thanks in part to the internet’s democratization of storytelling—anyone can write or film their experiences and put them online. And “telling one’s story”—in a novel or a film, a Twitter thread or a TikTok video—has also become disproportionately valorized, often seen as a “brave” way to generate empathy and political change. A more critically minded and media-literate populace is the only antidote for a culture in thrall to a good tale.

Read More: Top 25 Shows Based On True Stories